By Philip Hoare

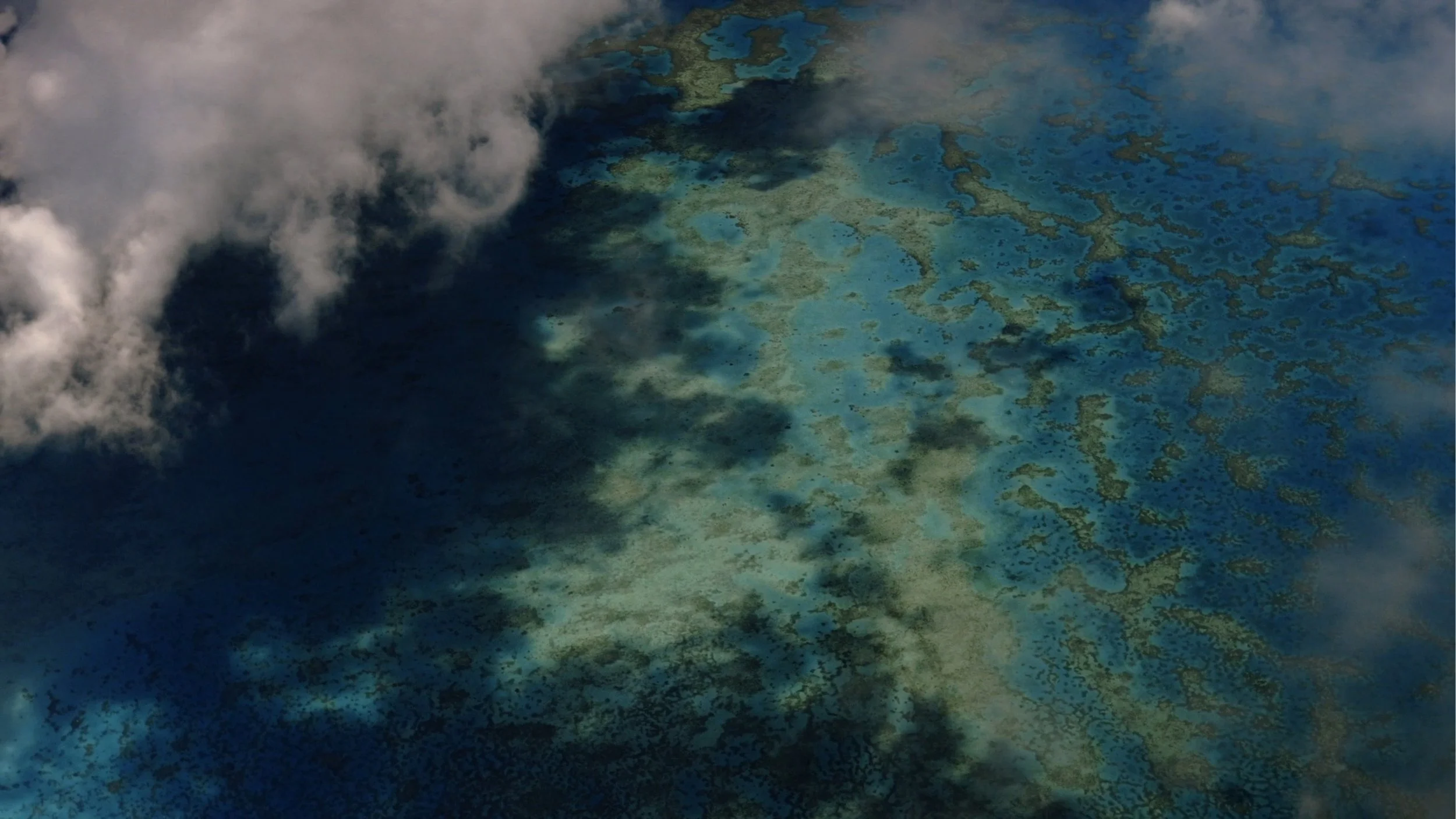

The recent stranding of 29 sperm whales on the British, German and Dutch shores of the North Sea comes as a kind of epic deputation from the deep. Cetaceans, by their liminal nature — air-breathing mammals like us, yet choosing to live in the alien environment of the ocean — seem to symbolise our collective disconnection from nature. I would contend that no other animal is so emblematic of the vexed distance between human and natural history; so laden with the way in which we ignore the ocean.

Strangely, there is a long history of these whales — the deepest diving of all cetaceans — stranding on North Sea coasts. The 16th century German artist Albrecht Durer was said to have died of a fever caught when he tried to reach a stranded sperm whale in the marshes of Zeeland. And a spate of sperm whale strandings in Holland in the 17th century was commemorated in Delft ware and numerous paintings and engravings. Other dead whales exploded, infecting spectators with what was assumed to be a fatal miasma.

These encounters were, for the vast majority of people, their only visions of whales. But their historical progress also spoke to the assumption of cetaceans within the scientific sphere, as if the vastness of these shape-shifting leviathans was gradually coming into focus. Even up to the mid-18th century the French Academy were diagnosing 14 different species of sperm whale.

There is only one. It wasn't until descriptions in the late 18th century by John Hunter and Georges Cuvier, and a little later, by Thomas Beale, that this particular species was firmly identified.

Most famously, a sperm whale stranded off Holderness in 1825 became the property of the local aristocrat, Sir Clifford Constable, of Burton Constable Hall, near Hull. Uniquely, he was allowed precedent over the whale, which elsewhere would have been automatically the property of the monarch — as whales stranded on English shores still are. The Holderness whale was articulated on an iron frame and exhibited in the grounds of Sir Clifford's estate. It has only recently been rediscovered and, restored, is now displayed at Burton Constable, where it boasts the unique claim of being the only whale described in Herman Melville's Moby-Dick which actually existed.

Melville, of course, is the modern iconographer of the mythic sperm whale. In 136 chapters, he celebrated everything he knew about sperm whales, which he had hunted himself. By the time he put to sea, in 1841, the sperm whale provided the oil which lit the cities of New York, London, Paris and Berlin, burned in lamps, and in the finest, smoke-free candles. Indeed, we owe the measure of light itself, the lumen, to the time it took these candles to burn.

It is a wonderful, terrible paradox that an animal of the darkest depths should have furnished us with light. The same oil lubricated the machines of the Industrial Revolution. Before the first commercial tapping of mineral oil in Titusville, Pennsylvania, 1859, the western world ran on whale oil. These animals were part of an economic, industrial process; they were, in their way, the first victims of the approach of the age of the Anthropocene. Up until the 1960s, European countries maintained whaling fleets. Ships arrived at my home town port of Southampton, laden with rendered down blubber which then entered the food chain as margarine. Sperm whales hunted in the Azores were turned into garden fertiliser. It wasn't until the end of that decade, when scientists Roger Payne and Scott McVay lowered their hydrophone into the waters off Bermuda and recorded the song of the humpback whale — a drifting, asymmetrical threnody, suggestive of an entirely new culture beyond our own — that a dumb animal was heard to protest its abuse.

We are still dealing with that sharp about-turn. The news headlines which greeted the North Sea strandings, the selfies and the editorials, are reminders of that ongoing story. Whales continue to speak to us from the sea. Sperm whales have the largest brains of any animal that has ever lived. They are sentient, socially organised creatures with a matrilineal culture, a highly developed

sense of communication and, it is now thought, an awareness of their abstract selves. One scientist has even suggested that they may have evolved their own rudimentary ideas of religion, to explain their place in the world.

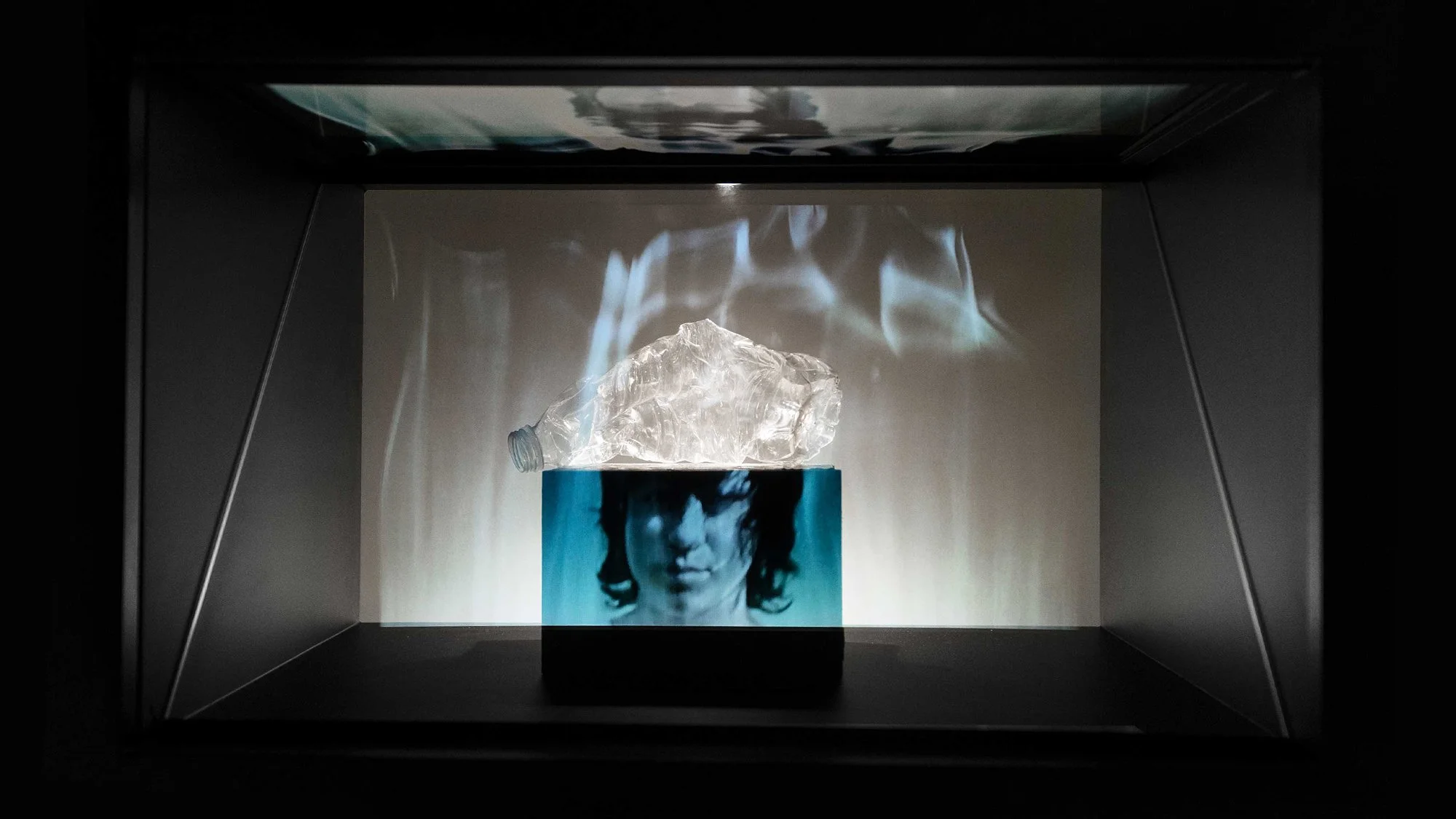

Whales challenge us. They bridge the gap between their environment and ours. Their loyalty to one another — defined by their collective individuality, their sense of community — is one reason why they appear on our shores; anthropogenic pollution, both chemical and aural, are also implicated. Sperm whales, because of where they sit at the top of the marine food chain, may be among the most polluted animals on the planet. Recent research at the University of Southern Maine, for instance, indicates that these deep-diving, deep-breathing cetaceans are inhaling chromium from coastal chemical plants in quantities fit to induce rampant cancer in humans. Others ingest plastics and other detritus which restricts their ability to feed.

Where we spent centuries hunting them, they now die as byproducts of our relentless desire for progress. As emissaries of the ocean, they represent the known and the unknown; reminders of our supposed dominion, and our apparent helplessness. Confronted with their pathetic demise on a winter beach, perhaps we are looking not at them and their fate, but at our selves and our own.

Philip Hoare is the author of Leviathan or, The Whale and The Sea Inside. @philipwhale

Photos by Jeroen Hoekendijk

Five things you never knew you loved about Physeter macrocephalus:

Sperm whales have remarkable memories and never forget their friends. (source)

They have the largest brains of any creature ever known to have lived on Earth. (source)

Like humans, they are self aware. Different clans, or pods, have different dialects, and individuals identify themselves by speaking in unique code. (source)

They’re world class divers and natural collaborators, using teamwork to hunt prey. (source)

Sperm whales are intelligent and sentient beings capable (and deserving) of loyalty and love. When one sperm whale beaches itself, its companions follow. And as Philip Hoare writes on the recent North Sea stranding, "It is in that loyalty, one to the other, that the root of this tragedy lies."

Learn more from the Parley Collaborator Network:

"The Whale: In Search of the Giants of the Sea" by Philip Hoare // Author and Parley Speaker

"Among Whales" by Roger Payne // Founder of Ocean Alliance

Sperm Whale Research by Ocean Alliance