Journey through the wonders of California's cold water kelp

By Ben Meissner

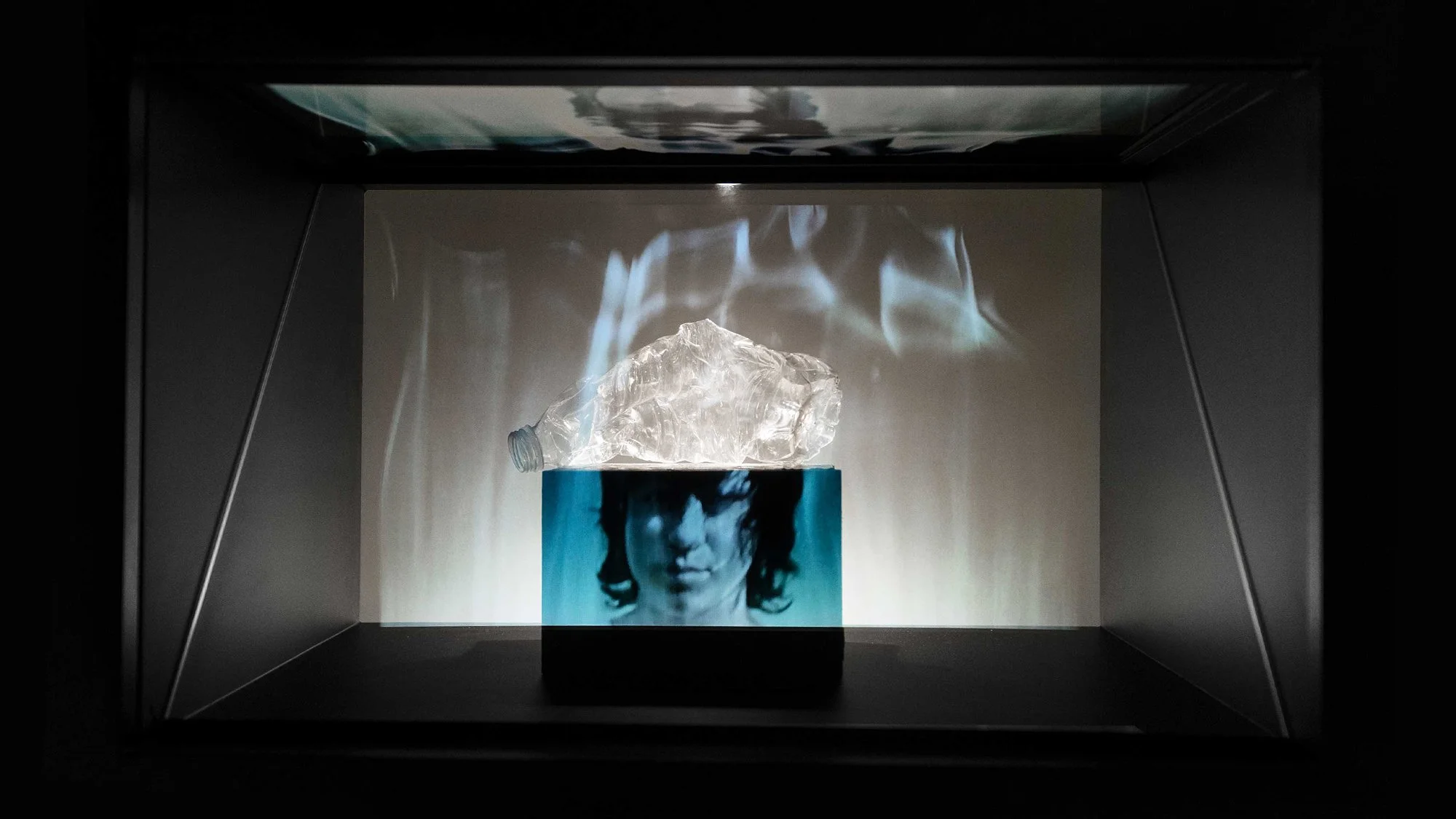

This winter the waters off Casino Point, Catalina Island, host new visitors. Suspended somewhere between an air-breather's realm and the ethereal world of shipwrecks, Doug Aitken’s buoyed constructs pull eyes and minds into the water column for quiet, oceanic contemplation. Three geometric pavilions anchored to the sea floor, paneled with rock and prisms, comprise this collaboration between Aitken and Parley for the Oceans, presented in partnership with the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA).

Underwater Pavilions beckons more oceangoers than usual to don neoprene, scuba tanks, anything necessary to temporarily visit the aquatic environment this winter.

As you exchange gravity and words for an eccentric experience, will silent floating reverie draw to mind wonders of our oceans that build themselves?

Similarly secured to the seabed and with no less complexity, the kelp forest aesthetic has been crafted over thousands of years of evolutionary thought. Macrocystis pyrifera (giant kelp) can stretch and sway to the surface at lengths over a hundred feet…but even with a size proportional to pine trees one might think it strange to discuss it as one of California’s forests.

Images by Kyle McBurnie

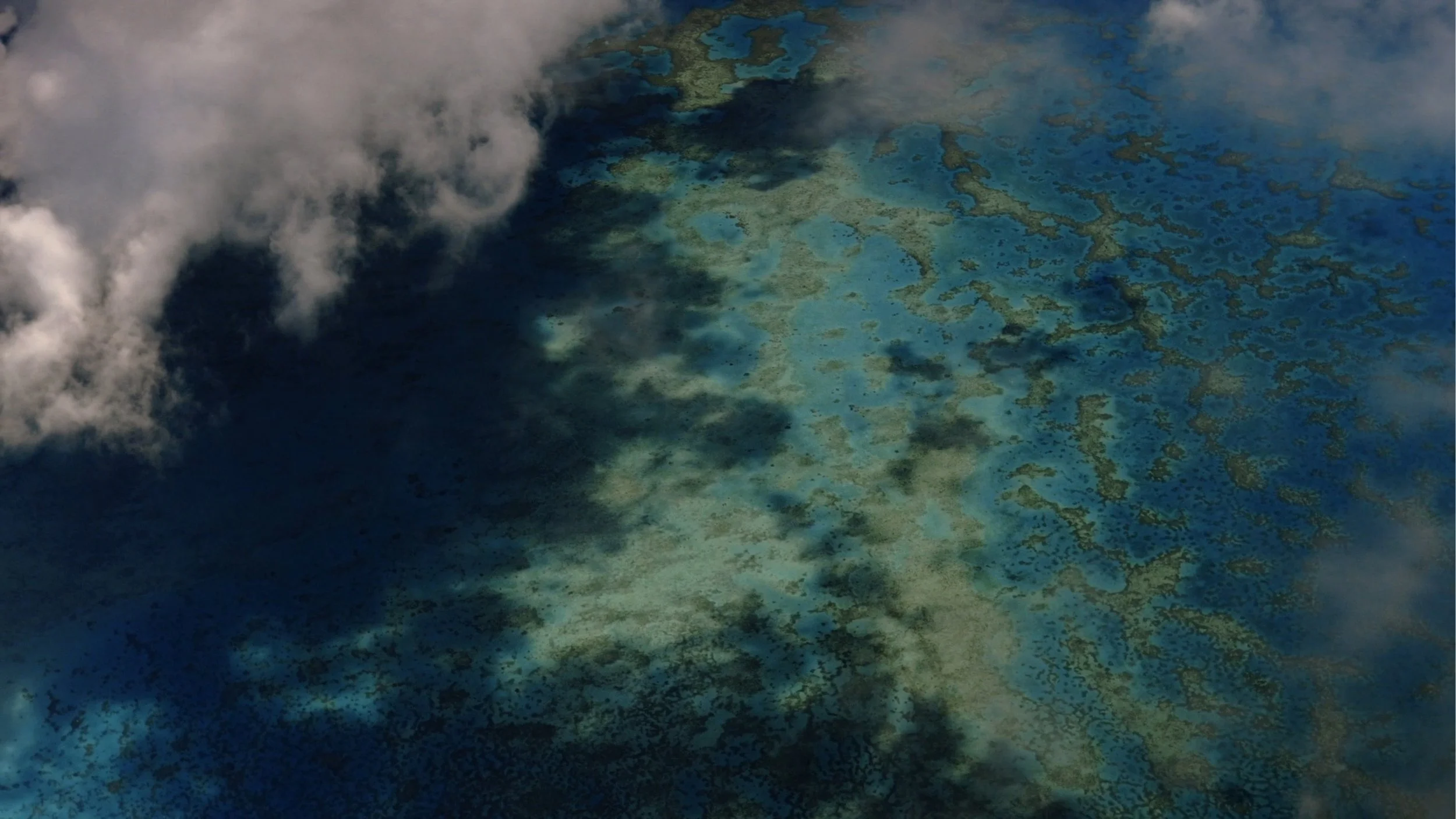

Kelp forests have no trees; in fact giant kelp isn’t considered a plant but rather classifies as an algae. The concept of a forest typically lends a sense of permanence and nostalgia, a place you can return to over the years, climbing the same tree, back to your roots. Kelp forests endure a more transient lifestyle. California’s kelp, a species found across the world in mid-latitude temperate oceans, thrives in cold nutrient-rich waters, blanketing the coastline with a deep olive green canopy so thick at the surface one might imagine walking across. Its fortitude truly makes the thought of people millennia ago using it for a land bridge believable. But when oceanic mechanisms bring extended periods of warm, nutrient-depleted water to these environments, it is harder for these forests to thrive. Climate drivers like strong El Niño (ENSO) years leave water temperatures in the Eastern Pacific abnormally high for longer stretches of time, stifling the kelp. The addition of stronger winter storm surge can tear the intricately designed anchoring system of external roots called “holdfasts” from the rocks to which they cling.

Despite quick departures, giant kelp regenerates with incredible vigor. It has been known to grow as much as two feet in a single day, vertically supported by hundreds of rubbery air-filled gas bladders that maintain its upright posture. The leafy, green textured fronds of kelp begin to deteriorate after about six months, breaking off to feed resident herbivorous fish in a process called sloughing as new fronds replace them. So while you might not find yourself returning to precisely the same olive green columns year to year, the forest persists.

"Be it lizard or lobster, land snail or sea urchin, underwater kelp forests host every bit as much life as their terrestrial counterparts. Yet we hardly show equal appreciation for landscape and seascape."

If you were to slip between swaying stalks of kelp on a calm sunny afternoon and walk across a seafloor scattering sunlight like shattered gold, it would be easy to declare yourself forested. No sparrows flitting from branch to branch, but flashes of vibrant orange Garibaldis chase one another between the green. No sleeping foxes tucked under fallen trees, but a docile horned shark rests peacefully in a rocky crevice. No ants marching by, but a Spanish Shawl nudibranch bursting with colors as cautionary and beautiful as a poison dart frog pulls slowly along the bottom, unhurried. Be it lizard or lobster, land snail or sea urchin, underwater kelp forests host every bit as much life as their terrestrial counterparts. Yet we hardly show equal appreciation for landscape and seascape. Perhaps the sheer inhospitality of a cold, wet, underwater wilderness prevents us from paying our dues to kelp forests as frequently.

"Kelp forests can exhibit levels of biodiversity similar to coral reef ecosystems.

Not only do they provide hideouts from potential predators, but also a haven of stillness when powerful underwater currents and storm surge rips across the open sand."

For that reason we must cherish these extra moments of contemplation brought on by Doug Aitken’s pavilions, a chance to appreciate these underwater ecosystems for the wealth of services they provide. Just like trees, kelp photosynthesizes to grow, providing oxygen and ingesting CO2.

Kelp forests shelter an enormous range of species, the aforementioned holdfasts alone housing between 30-70 different species of critters, the dense labyrinth of greenery providing sheltered habitat for everything from spiny lobster to giant moray eels. This level of biodiversity is akin to a coral reef. Not only is this environment a hideout from predators, but also a haven for animals less inclined to spend their life swimming—a stillness away from strong underwater currents that rip along across open sand. Like seeking shelter between sturdy trees on a blustery winter night, the formidable clusters of 60-foot tall algae stalks quiet ocean forces, creating a noticeable tranquility when one slips within their ranks. Our terrestrial communities reap the benefits of this energy absorption the same way islands in more tropical climates rely on coral reefs and mangroves as storm buffers.

In recent years, California’s kelp forests have been noticeably diminished due to longer periods of warm water in the Eastern Pacific, and ground lost to competition. Stretches of coast have been conquered by voracious colonies of purple sea urchins that blanket the seafloor, seizing every inch of real estate and preventing kelp from regaining a hold.

An invasive species of Asian seaweed known as Sargassum horneri also capitalizes on the dieback in giant kelp. As a hardier species in warm water with a shockingly fast rate of reproduction it has made a claim as a permanent resident of California’s waters since the early 2000s. Over the next several decades the replacement of giant kelp with Sargassum and other less vertically inclined species of seaweed could dramatically change the structure of these dense sea-havens that so many animals depend upon. Power struggles often go unnoticed on the surface, but cold-water forests live in constant flux.

Under the unassuming taxonomic classification of ‘seaweed’ kelp forests quietly persist, carving order out of chaos with a survival-prone nature that the marine world requires. And like any of its terrestrial counterparts, the concept of deforestation should sound troubling. If enough kelp dies off an ecosystem can experience dramatic change that impacts its ability to perform environmental services. Perhaps as we peer through Mr. Aitken’s prisms we may find glimpses of clarity and a newfound respect for the constant battle of life that ensues in our oceans. While life, death, and change are all parts of the natural cycle, man-made marine pollution from things like urban runoff and agricultural inputs are not. Our role must continue to be one of stewardship and protection if we wish to maintain this balance.

There’s a number of ways you can respect and protect kelp.

1. Visit and explore Underwater Pavilions

2. Understand the threats they face, and how what you do affects them.

3. Support sustainable harvest and cultivation of kelp forests.

Images by Kyle McBurnie