Legendary ocean explorer Jacques-Yves Cousteau famously noted that “People protect what they love, they love what they understand and they understand what they are taught.” Today, getting more people to explore and fall in love with the oceans is more vital than ever. Working at the intersection of art, photography, marine biology and computer science, The Hydrous is a non-profit organization on a mission to create “open access oceans” and give more people the chance to experience underwater ecosystems. With an international team of scientists, divers, designers, filmmakers and technologists who all love the ocean, the San Francisco-based project has been working to create unique 3D models of various reef species to enlighten and educate. Parley caught up with CEO, co-founder and marine biologist Dr. Erika Woolsey to find out more.

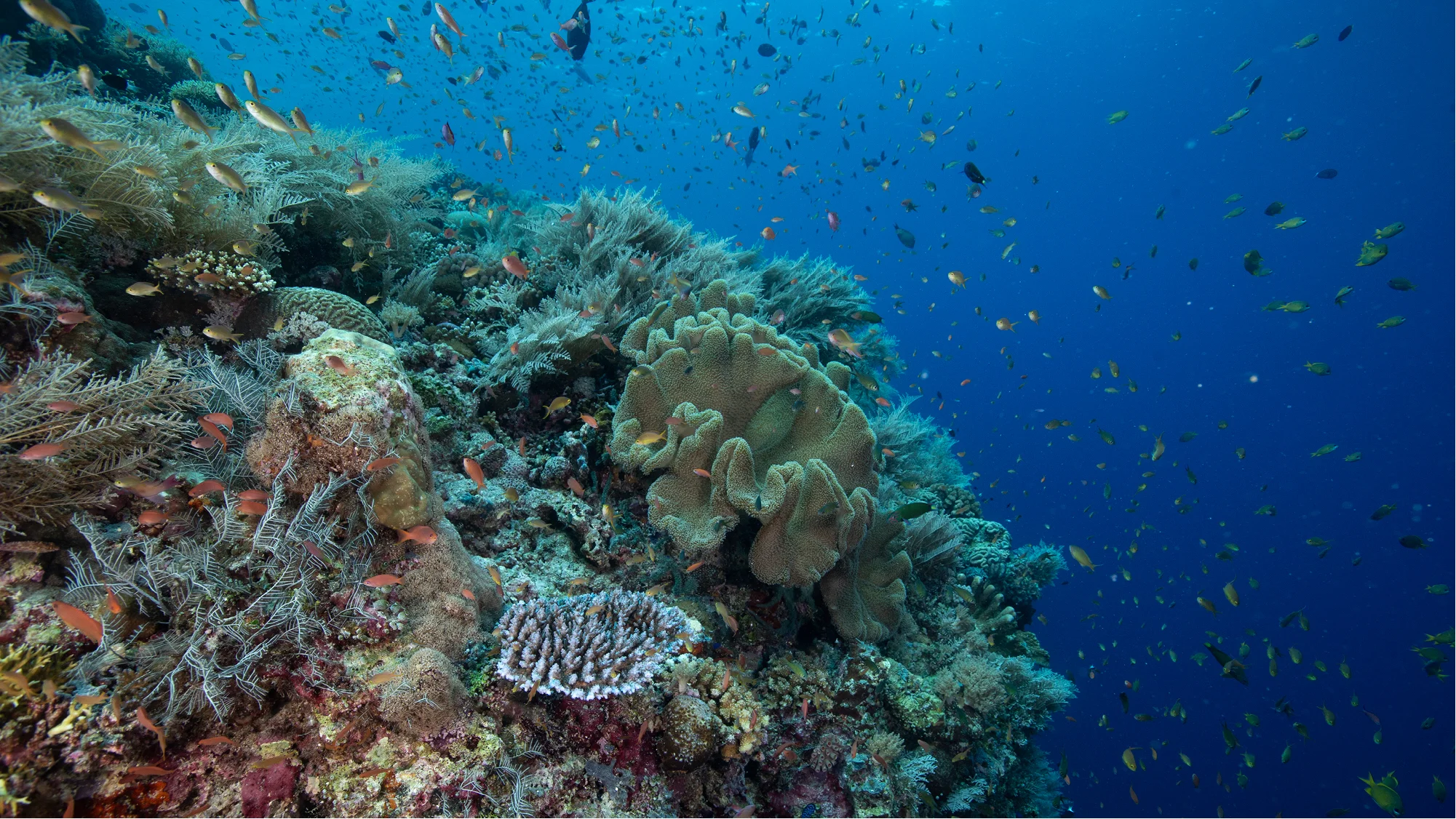

All photography by Rick Miskiv – Director of Underwater Photography for The Hydrous.

Why map and visualise coral – what can we learn?

The ocean is overexploited, under-protected, and out of mind. Underwater photogrammetry is a great way to collect and visualize coral reefs in a non-destructive way. Our 3D models of corals that we’ve collected on reefs around the world- and from museum collections- are open access as well as data rich (containing information like volume and surface area) and have been used by scientists as well as by educators, artists, and even video game developers. Not only is 3D modeling a great tool for monitoring coral reefs, it’s also an engaging way to bring these beautiful and threatened ecosystems into the public consciousness.

We include 3D printed coral models in our Ocean Kits that we are currently developing for middle school classrooms, in partnership with National Geographic. These models turn white when submerged in warm water (with different temperature thresholds by species and location, just like bleaching patterns in nature) and I’m so amazed by kids’ visceral reactions. I think it’s a compelling, tactile activity for young people to experiment and think about the effects of climate change on our blue planet.

In addition to 3D modeling coral reefs, the Hydrous is also creating an immersive virtual reality experience to take people on virtual dives. VR and underwater worlds are a match made in heaven and – while we can’t bring everyone to the ocean – we can use scalable technologies to bring the ocean to everyone.

Which areas have you studied so far, and have you noticed any changes in those places since the project began?

So far the most striking contrast we’ve seen on Hydrous expeditions occurred in the Maldives, in the Indian Ocean, between 2015 and 2016. In April and May of 2016, this region experienced a bleaching event that affected ~60% of Maldivian reefs. By the time we arrived in November of that year it was like viewing ancient ruins. The scale and severity of the event- which lasted only a few weeks- was mind-boggling and it was really hard to see a valuable habitat go from vibrant to somber in only a year.

What are we still learning about coral?

Thanks to the incredible advancements in molecular biology and genetic sequencing, we’re learning a lot of about how different species are related to each other and how they might (or might not) adapt to changing oceans.

All photography by Rick Miskiv – Director of Underwater Photography for The Hydrous.

What’s your own personal favourite coral species?

I actually have three! Acropora spathulata and Goniastrea favulus, which were two of my study species for my research on coral reproduction under warming temperatures. I had a lot of fun following their natural cycles and observing them spawn (an incredible phenomenon) over a few years. I also like Stylophora pistillata for more superficial reasons. It comes in gorgeous blues and pinks, and the polyps’ extended tentacles on its round branches make it look fuzzy and cute.

All photography by Rick Miskiv – Director of Underwater Photography for The Hydrous.

For more information, images and downloadable 3D models visit The Hydrous